Character Encoding

Introduction

How do we decode a character? Author James Lane Allen seems to think that it is adversity that reveals the character. But let us leave the decoding of human character to philosophers and social scientists and solve a more tractable problem. How do we decode a text that is encoded as a sequence of bytes?

The process of encoding textual data into a sequence of bytes is called character encoding and will be the topic of interest in this post.

ASCII

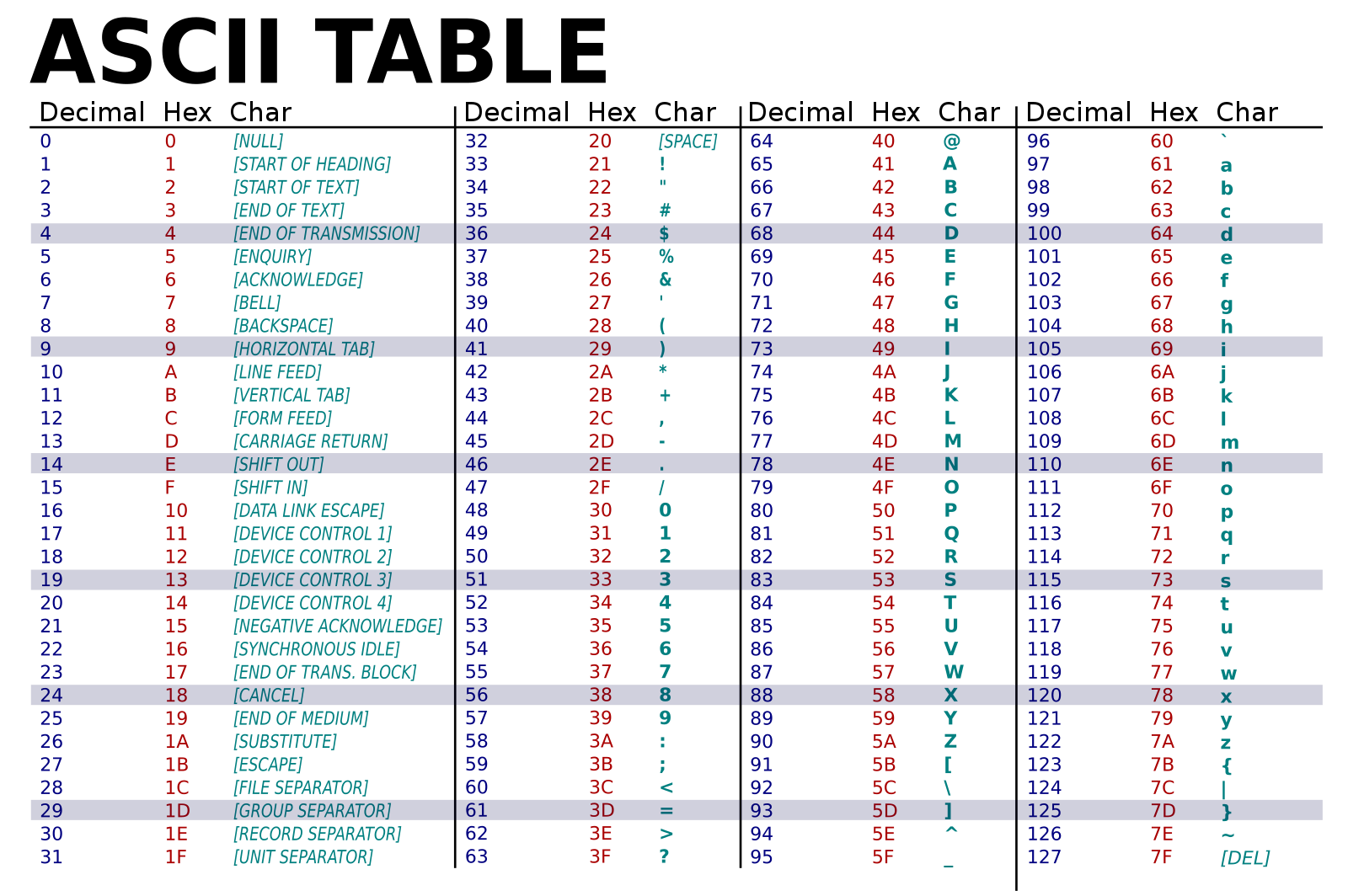

ASCII, American Standard Code for Information Exchange, is the most common character encoding that has been in use for the past 60 years or so. At the heart of it, it uses 8 bits for encoding characters. The first bit was traditionally used as a control bit and is obsolete now, it is now always set to 0. So, we have 7 bits that lets us encode 128 characters. Of these, there are 95 printable characters and 33 non-printing character codes. The 95 printable ones are predominantly the English alphabets (A-Z)(a-z)(0-9) and some punctuation symbols.

The easy way to think of this is that there is a big lookup table where each character is assigned one specific sequence of bits. For example, the sequence of bits 1100001 (61 Hex, 97 Decimal) represents the character ‘a’. I have reproduced the ASCII table from here.

The interesting question is this - are these assignments arbitrary or was there some good thought behind it. The answer, of course, is that this mapping was quite intentional. Let us look at the mapping for ‘A’ and ‘a’.

- A is Hex 41 0100 0001

- a is Hex 61 0110 0001

As we can see, there is just a one bit difference between the encoding of ‘A’ and ‘a’. So, it is very easy to convert from the lower case to upper case just by flipping the third bit. Similarly,

- 0 is Hex 30 0011 0000

- 9 is Hex 39 0011 1001

One can just get the ASCII encoding of a digit by just setting the the top four bits with 0011 or Hex 3. Pretty neat!

If we get a sequence of bits that we know has been encoded in ASCII, we can just separate out the bytes, look up that sequence in the ASCII table and get the corresponding characters for them.

For example, let us assume that we are given this sequence of bits 01011001011001010111001100100001 to decode.

- Split into sets of 8 bits. 01011001 01100101 01110011 00100001

- Look up in the ascii chart for each of these sequence of bytes

- 01011001 is 59 (Hex) that encodes character ‘Y’

- 01100101 is 65 (Hex) that encodes character ‘e’

- 01110011 is 73 (Hex) that encodes character ‘s’

- 00100001 is 21 (Hex) that encodes the punctuation mark ‘!’

So, the above sequence of bits represent the string “Yes!”

Unicode

ASCII, for all its adoption and efficiency, suffers from one big limitation. It uses only 7 bits to encode and hence is limited to encoding only 127 characters. There is of course a need to support characters from non English languages and other characters like emojis. To solve this, every country and community started using developing their own non ASCII character encoding techniques. This led to massive compatibility issues when such systems needed to exchange data. The Unicode consortium was formed to address this. Unicode consortium acts now as the standards body to character encoding. Just like the ASCII table, there is a massive unicode table where all the different characters (more than 1 Million of them) are published. However, instead of assigning bit sequences to these characters, the Unicode standard just assigns an index, called a code point, to them. These code points are of the form “U+”. The entire unicode code space has code points from U+0000 through U+10FFFF.

OK, we now have this giant Unicode look up table. But how do we actually encode them into bits and bytes so that systems can exchange data without any problems? For that, we will need Unicode encoding techniques. The two most popular encoding techniques are UTF-8 and UTF-16.

UTF-16

The primary problem with ASCII was that it could support only 127 code points as it had only 7 bits to play with. If we now increase the number of bits available to encode, to say 16 bits, we can now support 2^16 or about 65K code points. This was the basic idea of UTF-16. Just use 16 bits for every character.

There were a few technical problems with this:

- This is not backward compatible with ASCII. The first 127 code points, which just needed one byte with ASCII will now be encoded as 2 bytes.

- This is also related to the above observation. With UTF-16, English characters, which do form a lot of the content around the world, occupy twice the space than their ASCII encoded equivalent. This is space inefficient.

- Unicode now supports 1M+ code points. With 2 bytes, only 65K code points can be supported. So, UTF-16 evolved into variable width encoding with 1 or 2 16-bit code units with a complicated logic using surrogate pairs to support the full set.

UTF-8

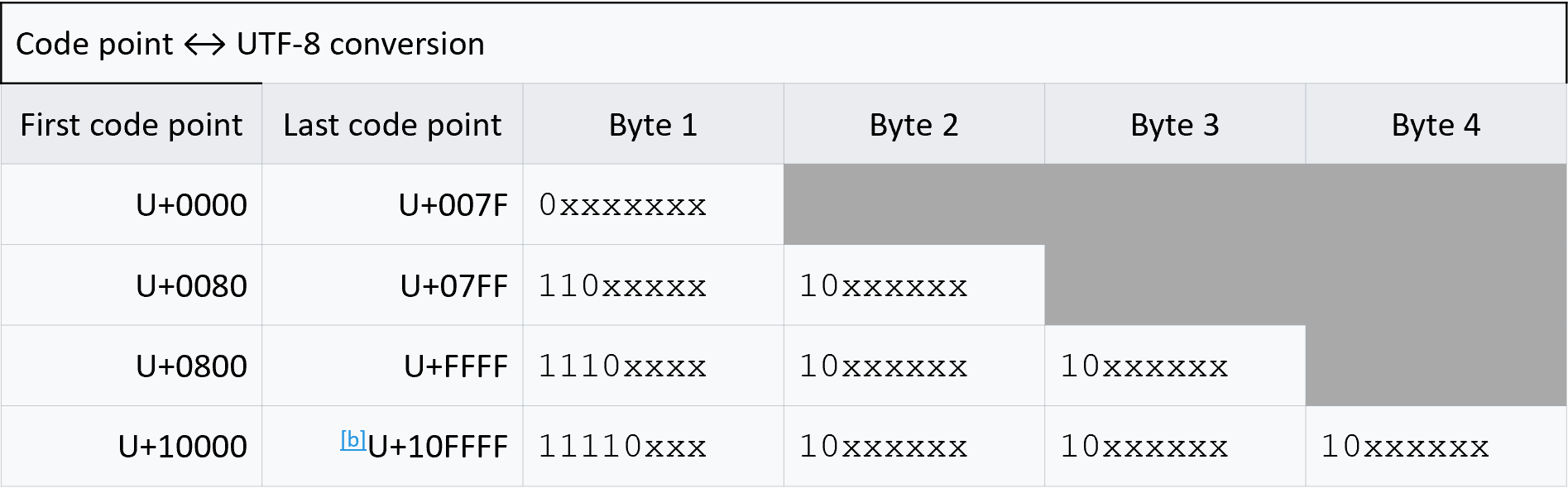

For the reasons mentioned above, UTF-8 was created. This is such an elegant solution as explained in this great video. It basically uses a variable length encoding that uses the minimal number of bytes that is needed to encode a particular code point. For example, the first 127 code points are encoded exactly as they would be in ASCII. The following table explains how the code point to unicode conversion happens.

For code points 0-127, UTF-8 encoding is identical to ASCII encoding, which makes it backward compliant. For code points between 128-2047, we use two bytes. The leading bits of the first byte read 110 and the leading bits of the next byte reads 10. The remaining 11 bits (5 in the first byte and 6 in the second byte) is used to encode the code point. For code points between 2048 and 65535, 3 bytes are used for the encoding with the leading bits in the first byte reading 1110 and the leading bits for the continuation bytes read 10. Similar logic is used for the four byte encoding as well.

Because it is backward compatible with Ascii and is also space efficient, UTF-8 is the most prevalent encoding that is used in the world today.

Let us try and encode a character using UTF-8 to understand how the process works. Let us encode the Devanagari character अ. This has the code point U+0905 (or Decimal 2309). The way we do this is as follows.

- 0905 is 0000 1001 0000 0101.

- Identify the number of bytes needed for this encoding. Since this is 2309, which is greater than 2048, we will need 3 bytes.

- A 3 byte UTF encoded sequence has the following format (See the table above) 1110 xxxx 10yy yyyy 10zz zzzz

- So, fill in the bits from 3 into the x,y and z in 2, from the back.

- This will give us 1110 0000 1010 0100 1000 0101. This is E0 A4 85,

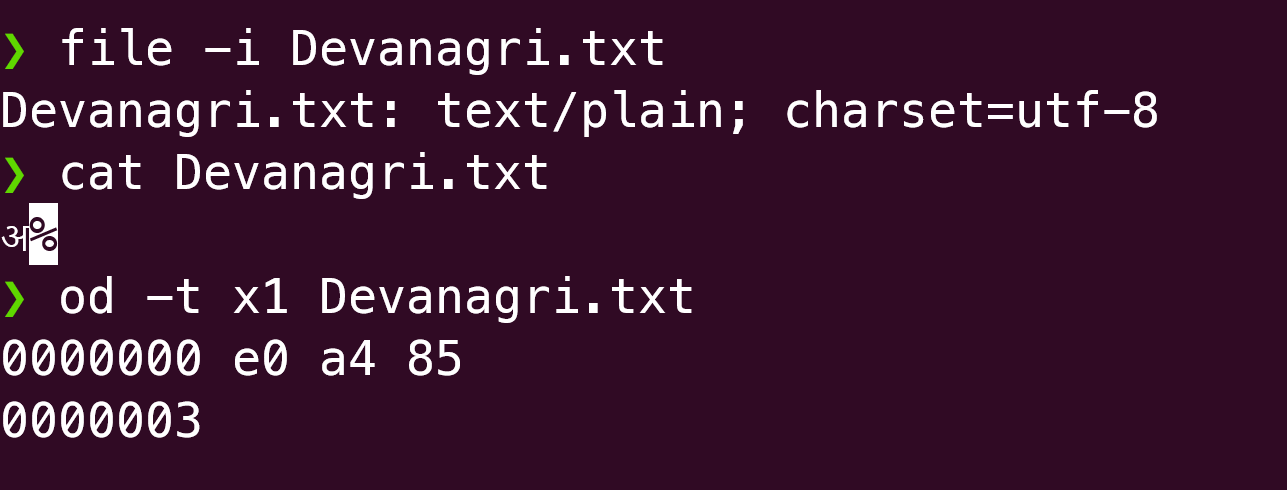

We can easily verify this. Let us create a file, called Devanagari.txt that has only one character, अ, in it. Then we can examine its contents by using the octal dump (od) command

As we can see, od shows the same sequence of bytes that we arrived after our encoding exercise.

Let us also do the decoding exercise once. Let us decode this sequence of bits F09F8D8ECF80.

- If we write F09F8D8ECF80 out - it reads 1111 0000 1001 1111 1000 1101 1000 1110 1100 1111 1000 0000

- The first byte starts with 1111 indicating that it is a 4 byte encoded character.

- Hence the first character is encoded as 1111 0000 1001 1111 1000 1101 1000 1110

- If we strip of 1110 from the leading byte and 10 from the continuation bytes, we end up with 0 0001 1111 0011 0100 1110. This is U+1F34E. This is the symbol 🍎.

- The second character that starts with 1100 and hence is a two byte character. This is 1100 1111 1000 0000. We follow the same process - strip 110 from the first byte and 10 from the second. This then reads U+3CO. This is the symbol π.

- Hence the above string, when decoded, leaves us with a pleasant taste in the mouth as apple pie.

UTF8/16

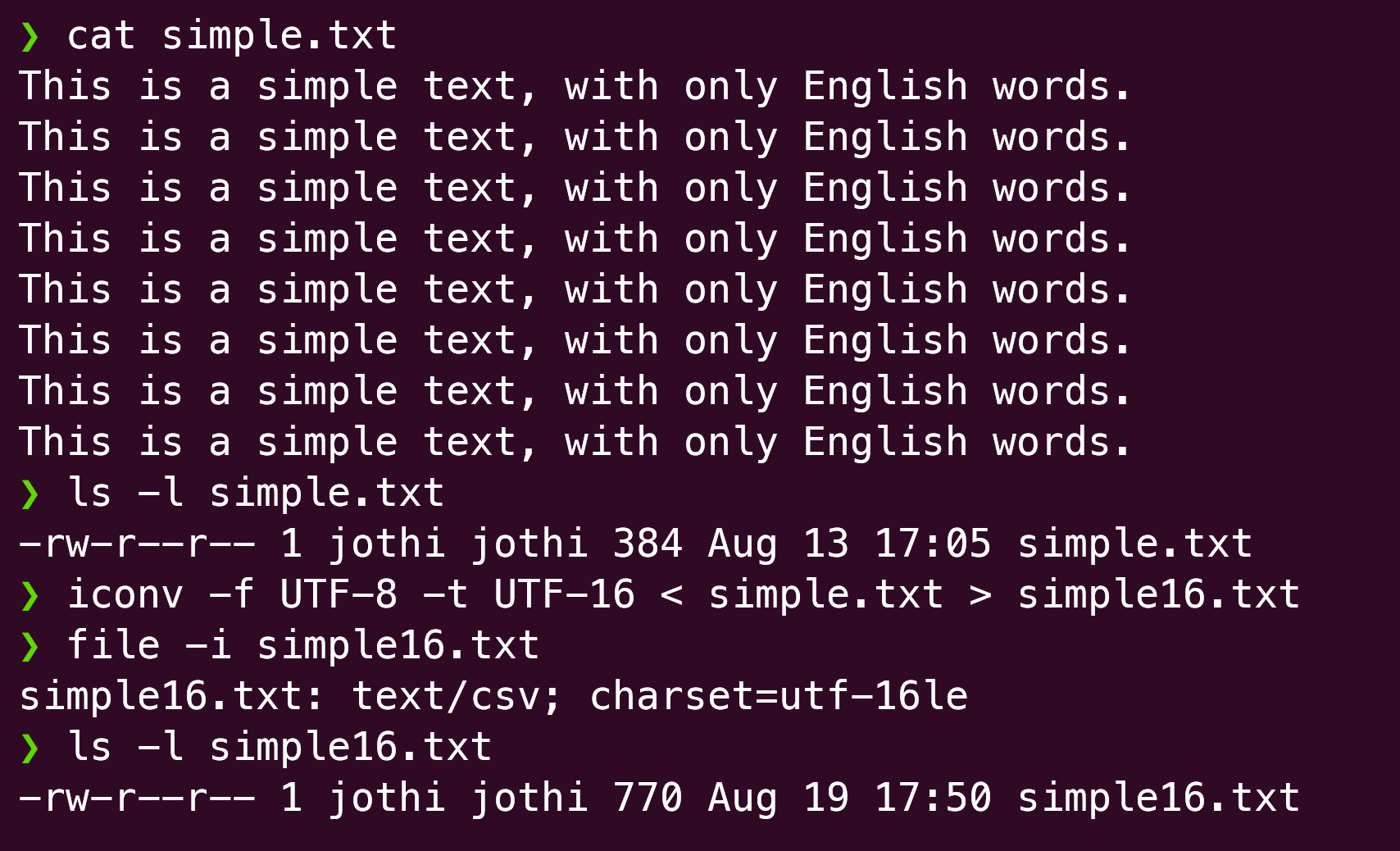

UTF-8, as we saw above is more efficient in terms of its compactness than UTF-16. But is this true always? For the first 127 code points, this is clearly the case. If we have a file with purely English characters, UTF-16 encoded file is likely to be around twice the size of UTF-8 encoded one. Let us check this out.

iconv is simple utility that lets you convert from one format to another. As we can see, the size of simple-16.txt is nearly double that of simple.txt.

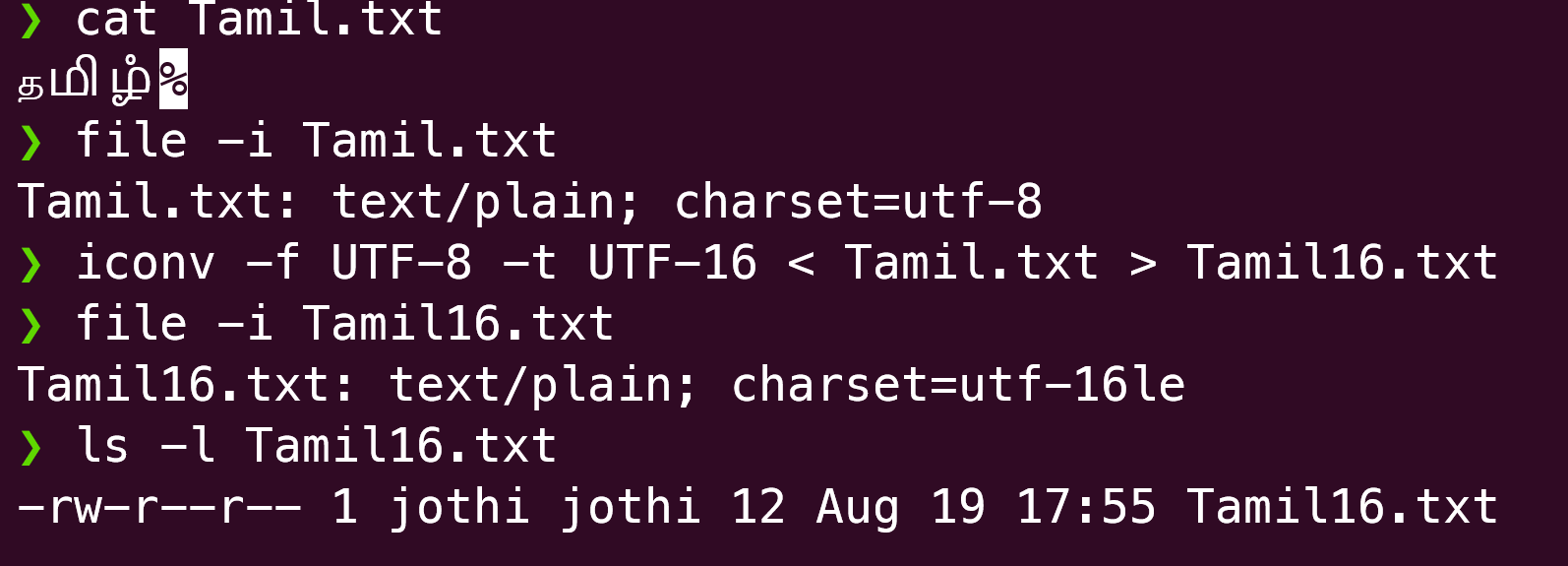

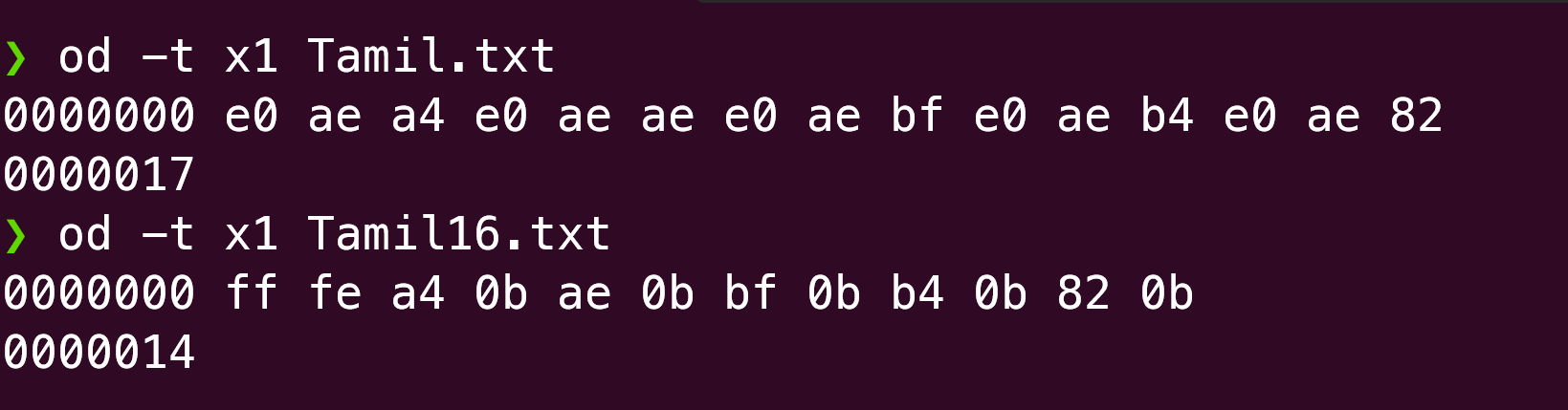

Now, let us take a file that is in a foreign language and repeat this exercise.

Here, we see that the UTF-16 encoded file is smaller than the equivalent UTF-8 one. That is because the characters that we encoded were ones that needed more than 11 bits (code points > 2048). For these, UTF-16 will just use 2 bytes for each unicode character whereas UTF-8 will need three.

There is an interesting observation for the discerning eye. The Tamil.txt file has 5 unicode characters (த,ம,ி,ழ,ஂ). The UTF-8 encoded file has 15 bytes, 3 bytes each for the each character. But the UTF-16 encoded file has 12 bytes, instead of 10 bytes. That is because there is a 2 byte header at the beginning of the UTF-16 file. This is called the Byte order mark (BOM) which is used to denote the “endian”ness of the encoding. If it is ‘FEFF’, it is big-endian encoded and if it is ‘FFFE’, it is little-endian encoding. In this file, we see ‘FFFE’ which denotes that this is encoded using the little-endian format. While UTF-16 files mandatorily have this BOM, it is optional for the UTF-8 encoded files as there is no alternative sequence of bytes in a character. This article gives a good overview.

Coming back to our discussion, in general, for code points between 2048 and 65536, UTF-16 will be more compact than UTF-8 because it does not use those control bits (leading 1’s in the first byte and 10 in the continuation bytes).

Summary

In this post, we tried to give a taste of what character encoding, Unicode and the Unicode encoding techniques, UTF-8 and UTF-16. While we use UTF-8 all the time, it is possible that we might not have paid much attention to the details behind this fabulous encoding scheme. Hopefully this post helped with gaining that much better understanding.